The Twosome Delusion

I’ll start with a radical statement: we are delusional, each and every one of us.

I’ll start with a radical statement: we are delusional, each and every one of us.

Culturally delusional, too.

How so? Because we have this notion of a single, unitary self when that’s not actually what we are. This has profound and subtle effects on how we are, and who we are, in our intimate relationships.

The cards are stacked in favor of our making this mistake. We’ve got one body, which implies one self, and on top of that our language uses the first person singular, not plural, to describe us. I’m “I” or “me,” not “us” and “we.”

The body lies. Our language lies. We have multiple selves crowding inside our one body and one “I.” It’s like a 19th Century tenement there inside us. I’ll use myself as an example. I have a confident self that can do no wrong, an uncertain self that’s constantly worrying about screwing up, an outgoing self who has a great time hanging out with other people, a brooding self who views social encounters as fundamentally unnourishing, a do-gooder self who cares deeply about the state of the world, a selfish self who cares first and foremost about The Moi, and–well, I could go on and on.

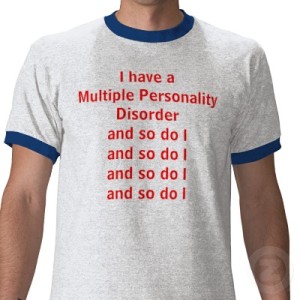

I’m not alone in this. We’ve all got multiple personality disorder, except it’s not a disorder, it’s part of the natural order. Psychologists describe people as “conflicted.” Not exactly: I’m not one person divided, I’m two (or more people) disagreeing. Apply the multiple personality model of the self to intimate relationship and it can get strangely liberating.

First, it suggests monogamy is a fiction. Think you’re in a relationship with just one person? Think again. One of my -exes and I used to have subpersonality dates. Boy, did I have fun with her dive-bar self! I wasn’t cheating, but it was as if I were going out with a different person. It offered the rush of the new and was a great change of pace.

Second, communication can get fundamentally more honest, assuming we have the courage to go where the multiple personality model takes us. In Unitary-Self Land, “I” am supposed to love my partner through and through, in every fiber of my being. I’m supposed to feel this way even in the face of contrary evidence, like when that thing he does makes me totally nuts, or those phases I go through when I wish he’d take a really long vacation to, say, Antarctica. And maybe fall in love with a penguin.

The multiple personality model helps us make sense of these contradictions. Many of me loves my partner, some of me is annoyed by her, and a couple of characters in there wish she would !@#$%^&* go away! The multiple personality model not only opens our internal landscape in this way, it tells us something important about these feelings (or, more exactly, selves)—specifically, that there’s nothing wrong with them. We don’t have to feel guilty when we’re not feeling in love with, or particularly loving of, our partner. It’s inevitable and nothing to fret about—part of the multiple-personality natural order of things.

When these negative feelings arise, what we need to do is a) remind ourselves that this isn’t how “I” feel and that there are still many partner-loving selves inside us, and b) wait for that unloving sub-personality to stop driving the car—or better yet, proactively take steps to swap out that angry or distant character for a more loving self. She’s there, most likely. We just need to find her.

We need accurate models to make wise choices. Because the unitary model of the self is inaccurate, it muddies our understanding of who we are and how we tick. It also feeds guilt because it encourages the notion that our one true self should behave in one “best” way and that anything short of that constitutes a failure or betrayal.

No! We have many selves, and they are all legitimate, and we need to honor and cherish all of them. And hide the keys sometimes.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!